The father of a 21-year-old man murdered in the Omagh bomb has told an inquiry into the atrocity of the last time he saw his son alive before the blast.

Aiden Gallagher went into the town centre along with his close friend Michael Barrett on August 15, 1998, to buy a new pair of jeans.

That afternoon, the Real IRA detonated a 500lb bomb in the busy market town that killed 29 people, including a mother pregnant with unborn twins.

Aiden’s father, Michael, who has spent years campaigning for answers on behalf of the families who lost loved ones in the blast, gave evidence to the public inquiry this morning and described his son as the “joker of the pack”.

“He was a normal young person,” Michael said. “He went out on the weekend with his friends. He enjoyed having a beer and having fun.

“He had a very wide group of friends from different backgrounds and interests.

“Aiden would have been the joker in the pack, there is no question about it. He was fun to be with.

“He enjoyed fun. He enjoyed company. If there was somebody in the crowd who was backward or didn’t like to come forward, he would notice that and would engage with that person.”

Michael recalled how his son loved working with cars and was a perfectionist when it came to getting things right.

He described how, as a child, Aiden would often dismantle toys and reassemble them to gain an understanding of how they worked, and he described how he maintained strong family bonds — particularly with his grandfather, with whom he shared a birthday, and his mother.

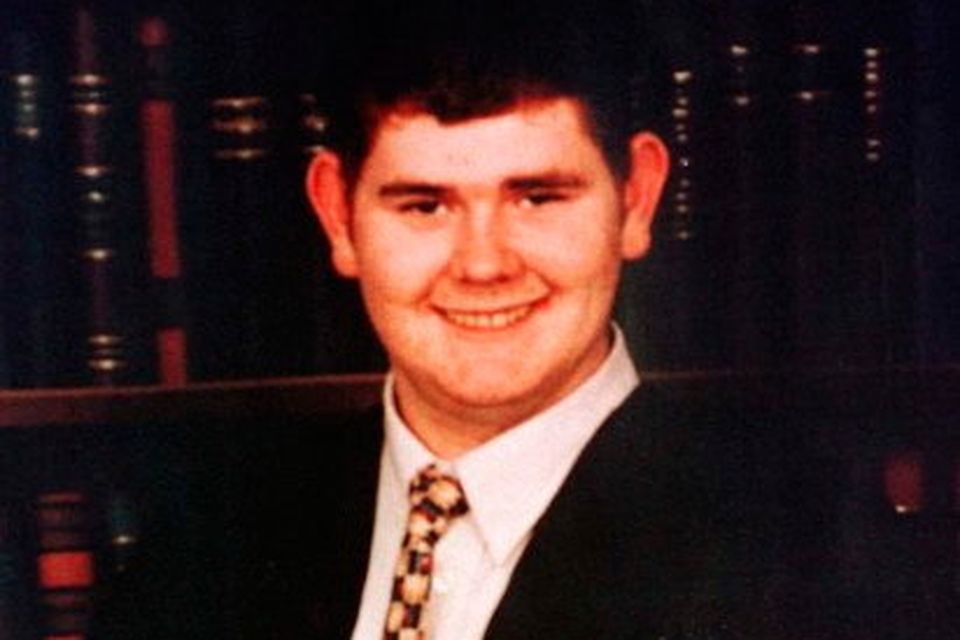

Michael Gallagher, whose 21-year-old son Aiden died in the Omagh bomb (Pic by Arthur Allison/Pacemaker Press)

“When he would be out with his friends at night and come in in the early hours of the morning, he would come in and sit on his mother’s side of the bed,” Michael said.

“He would talk about that night, how he enjoyed himself, who he saw and where he was. I would say: ‘Can we not speak about this in the morning?’”

“There was only one man in Patsy’s life and that was Aiden. There was only one woman in Aiden’s life and that was his mother.”

Even on the day he died, Aiden had been asking his mother for advice about clothes sizes and had “a pleasant conversation” with his dad, who remembers telling him where to park the car.

“He turned around and walked down the hall. I remember he looked back for the last time and said: “I won’t be long.’ That was really the last time we saw Aiden,” Michael said.

The heartbroken father was working on a car later that afternoon when he heard the explosion and headed straight out to look for his son at the hospital and leisure centre.

Within hours, he was called into a room with two young police officers.

“They started asking me questions about Aiden’s height, identifying marks and the clothing,” Michael said.

“I knew by the nature of the questions that it wasn’t going to be a good outcome.

“A short time later, we were told to go to the temporary mortuary, which had been set up at Lisanelly Army Camp. James went with me and we identified Aiden.

“I remember driving home in the early hours of the morning. It was starting to break day and I could hear birds singing in the trees.

“It seemed a normal situation but my greatest concern was how I was going to tell my family Aiden was dead.”

Thousands of people attended Aiden’s wake over the following days.

At his funeral, both the church and the car park were packed.

Michael said the presence of three clergymen from different denominations at the service provided him with much comfort.

“Fr Kevin Mullan was the officiating priest at the service. On the altar with him was the local Presbyterian minister, and on the other side was the local Church of Ireland minister,” he explained.

Aftermath of the Omagh bomb

“It was hugely important. There were politicians from both jurisdictions, but, more importantly, ordinary people from both jurisdictions.”

After Aiden’s death, Michael became involved with the Omagh support group.

Following a question from lead counsel to the inquiry, Paul Greaney KC, Michael spoke of the impact it has had on his life.

“If I have a regret, it is that I would have liked to, and probably should have, spent more time with my own family and less campaigning,” he said.

“It seemed to be the way things worked out. We don’t have the benefit of hindsight, but I do think I would personally have benefited if I had done less campaigning.

“That’s a hugely difficult but honest thing that I have to say. If there is a consolation in all of that, it’s the fact we are here today.

“I’ve sat through all of the testimonies and [they have] moved me enormously. To put a human face to the person, rather than a statistic, has been one of the consolations.

“I do hope we will continue to answer some of the very difficult questions we haven’t had answered so far.”

Read more

News Catch Up – Tuesday 4 February