Despite just one four-year and somewhat unorthodox term in office, Jimmy Carter brought much hope to the White House during a tenure that was marred by several major crisises.

As America’s 39th president, he emphasised human rights in his foreign policy, championed environmentalism at a time when it was not yet popular, and appointed record numbers of women and people of colour during his administration, which lasted from 1977 to 1981.

Several major events transpired during Carter’s presidency, notably the US energy crisis, the Iran hostage ordeal, the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, the Camp David Peace Accords and the Soviet-Afghan war.

Many viewed Carter, who grew up selling peanuts as a teenager on his family’s land in Plains, Georgia, as an unlikely candidate for Commander-in-Chief, and some critics later dismissed his tenure as a “failure”.

However, Carter had a long history of local and state politics before even arriving in Washington DC, and eventually claiming the Oval Office.

By 1969, he had served on the Sumter County school board, in the Georgia state senate and made an unsuccessful bid for Georgia governor.

To win the gubernatorial election in 1970, Carter adopted more conservative positions.

But rather than invoking traditional Southern values, Carter surprised his Georgia constituents by calling for an end to racial discrimination in his 1971 inaugural address.

His support of civil rights would later be a hallmark of his presidential campaign.

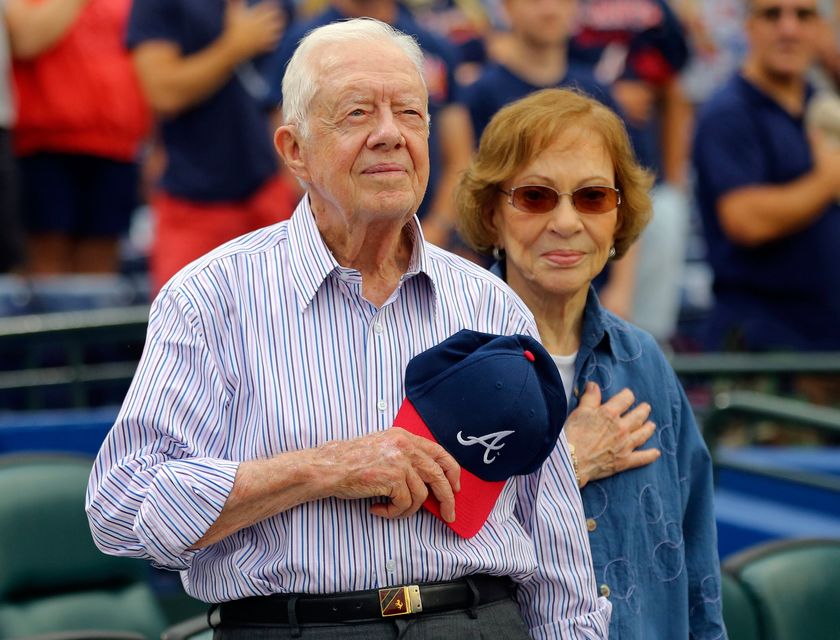

Former President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, stand for the national anthem before a baseball game between the Atlanta Braves and the San Diego Padres, June 10, 2015, in Atlanta (AP Photo/John Bazemore, file)

Barred by state law from seeking a second consecutive term as governor, Carter made another quantum leap and ran for president as the country was reeling from its disastrous Vietnam War, Watergate and the resignation of Richard Nixon.

As a relative unknown, even among his own party, Carter was considered the most improbable of long shots.

During his campaign he would reportedly often start with the phrase: “Hello, my name is Jimmy Carter, and I’m running for President.”

However, his tireless campaigning and his promise that “I’ll never lie to you” appealed to voters.

After a gruelling series of state primaries in early 1976, he won the Democratic nomination over a field of better-known candidates.

In the autumn of 1976, Carter narrowly defeated Republican incumbent Gerald Ford.

In a respectful address on November 3, 1976, he congratulated Ford, describing him as “the toughest and most formidable opponent that anyone could hope for,” and promised to unite the nation.

Carter took office on January 20, 1977, and emphasised his populist message by walking, with his wife and four children, nearly two miles from the steps of the Capitol to the White House.

His presidency was mired, however, by several major turns.

As his first order of business, Carter granted official pardons to hundreds of young Americans who had evaded military conscription during the Vietnam War. The measure was designed to heal some of the wounds that divided the country.

One of his biggest downfalls was that Carter was not a compelling speaker.

Combined with economic stagnation, rising inflation and a high unemployment rate he faced throughout his presidency, he failed to adopt widespread public support.

He was also uncompromising as an executive, putting him into conflict with members of Congress, even in his own party.

Carter failed to win passage of many measures he endorsed, including attempts to revise the tax system, reform welfare programs, control the cost of health care and provide for national health insurance.

Notably, in a struggle that lasted almost as long as his presidency, Carter fought over an energy programme that was structured to make fuel expensive enough that consumers would be encouraged to conserve it.

By the time he appeared in a cardigan for a nationally telecast speech to encourage energy conservation before that first winter was over, Carter was the butt of jokes.

Carter delivered this speech, often referred to as his “Malaise Speech,” on July 15, 1979, while the country was in the midst of a full-blown energy crisis.

In it, he said that everyday Americans were suffering from a “crisis of confidence”.

There were few other imaginative programmes on the home front, leading one Carter aide to lament, halfway through the administration, that the White House was suffering from “terminal narcolepsy”.

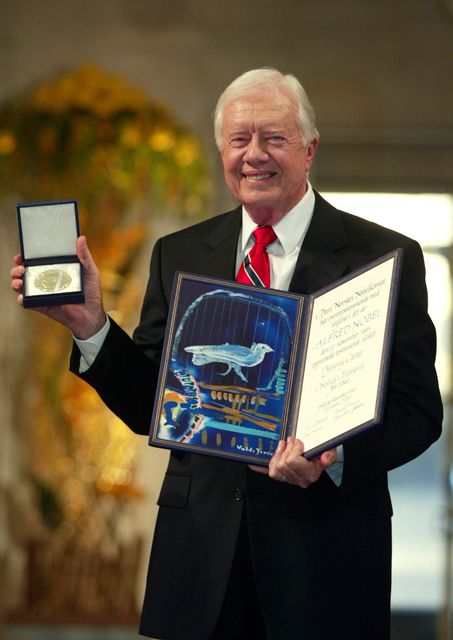

Former President Jimmy Carter receives the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo City Hall in Oslo, Norway, December 10, 2002 (AP Photo/Bjoern Sigurdsoen, Pool, File)

Where Carter found more success was in foreign policy, which he grew more enthusiastic about as his presidency progressed.

He built upon the work of Nixon by formalising relations with China, ushered agreements that give Panama sovereignty over most of the Canal Zone, met with the Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev to sign the nuclear arms control agreement known as Salt II and delivered the Camp David peace accords between Egypt and Israel in 1979.

His unyielding policies preserved the climate that isolated the Soviets and contributed to the end of the Cold War a decade later.

However, ultimately, what became cemented in Carter’s legacy were the failures of the Iran hostage crisis, when mobs ransacked the US embassy in Tehran capturing 52 people and holding them hostage for the duration of his presidency.

In a bold attempt to save the hostages, Carter organised a rescue operation that resulted in disaster when an American military helicopter crashed into a plane waiting to ferry the hostages to freedom.

“It was my decision to attempt the rescue operation. It was my decision to cancel it when problems developed in the placement of our rescue team for a future rescue operation. The responsibility is fully my own,” he said in an address to the nation.

The tragedy left an enduring impression on Carter that ultimately contributed to his failed re-election later that autumn – he was trounced by Ronald Reagan in the 1980 race.

However, Carter described the day he yielded office to Ronald Reagan in 1981 as “one of his happiest” because the hostages were freed.

Though Carter remained active in the Democratic Party, he never again sought elective office and preferred to live, out of the limelight, at his home in Georgia.

Carter died on Sunday, December 29, at his home in Plains, Georgia, aged 100.