On a pleasant afternoon, Martina Devlin is happy to be in the People’s Park in Dún Laoghaire, but not only because of the warm breeze and blowsy flowerbeds; this, she tells me as we sit sipping coffee, is the place where Charlotte Brontë first set foot in Ireland in 1854, disembarking the steam packet from Holyhead into what was then known as Kingstown.

She was on her honeymoon, having married her father’s curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls, an Irishman keen to introduce her to his family. The couple took the train into Westland Row station, and spent several days in Dublin, visiting Phoenix Park and Trinity College, where Nicholls had studied. Thereafter, they travelled to Banagher in what is now Co Offaly, to the area that Charlotte’s husband regarded as home and which forms much of the backdrop to Devlin’s intriguing and absorbing novel, Charlotte.

But Devlin was interested in more than simply narrating the last part of Brontë’s eventful life — she was to die, along with the couple’s unborn child, only nine months after she had married, at the age of 38. She also wanted to explore the Brontë family’s ambivalent relationship to Ireland and what it reveals about their life, the work and wider attitudes towards the country.

In the novel’s opening pages, Charlotte is approached by “a hollow-chested girl carrying a baby almost as large as herself”, beseeching her in Irish. Arthur’s cousin Mary, a central character in the novel, translates: “She’s saying they’re hungry. They’re the only two left from a family of eight.” But while Charlotte finds the scene harrowing, Mary reflects that she must “guard against allowing my heart to harden”, given that destitution is everywhere. “The people had become walking skeletons — those who’d survived. Between death and emigration, the country had emptied out.”

Devlin points out that Black ’47, the worst year of the Great Famine, was the year that Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë’s most famous novel, was published, under the gender-disguising pseudonym Currer Bell. Emily Brontë/Ellis Bell’s Wuthering Heights and Anne Brontë/Acton Bell’s Agnes Grey also appeared in 1847.

“England was full of people from Ireland fleeing the famine”, explains Devlin, and they were frequently greeted with horror and contempt rather than sympathy: “Charles Kingsley, who wrote The Water-Babies, talks about ‘human chimpanzees’, the Punch cartoons at the time present Irish people as simian. It’s about colonisation: people aren’t capable of ruling themselves, and the famine was an act of God.”

The Brontë family had a clear and strong link to Ireland. Patrick Brontë, father of Charlotte, Emily, Anne and three other children, was born in Co Down in 1777; his father, Hugh Brunty, was an Anglican, his mother, Elinor McClory, a Catholic. They had very little money, but Patrick managed to forge a different path, and ended up as a “sizar” — a student who exchanges labour for financial aid — at the University of Cambridge.

It was there that “Brunty” became “Brontë”: “He reinvented himself, and he never quite gave credit, I think, to the people who had helped him, because he didn’t get from Co Down to Cambridge without help. There was a Co Wicklow-born minister called the Reverend Thomas Tighe, from a very famous family, who took him on and helped him to Cambridge to his college, St John’s, and another clergyman in the Co Down area. They saw this very bright young man — legend has it that they found him reading Paradise Lost and doing all the voices. So he got part of the grant, but he had to work his way through. It cannot have been pleasant being a servant there, and also doing lectures and trying to win prizes for the money.”

But Patrick Brontë’s Irishness was somewhat glossed over, particularly, Devlin points out, in Elizabeth Gaskell’s mythologising, posthumous biography of Charlotte. “She wrote that there was nothing of the Irish in his voice”, Devlin tells me, “which was patently untrue. And she also said that he wasn’t in touch with his family back in Ireland, which was also patently untrue. They wrote to each other, and he would remember them in his will. He sent them copies of Charlotte’s books: there was that connection.”

Great courage: Charlotte Brontë

I ask Devlin what first drew her to writing about Charlotte Brontë. “I suppose it all began with Jane Eyre,” she replies. “I loved Jane Eyre as a kid and as a young woman. I was intrigued by this unassuming governess. She’s not egotistical, and yet she can’t be pushed around. And it’s one of the most famous phrases in literature, those four words, ‘Reader, I married him’: in the last chapter, she tears down a wall between the written word and the reader, and you hear her voice. So I loved the novel. My view about Mr Rochester changed as I aged — as a young woman, I thought he was fantastic and much better than a Jane Austen hero, because he had feet of clay.

“But as I got older, I realised that he was an attempted bigamist, then he wanted to set Jane up as his mistress and that his ward, Adele, was clearly his natural daughter. And then I read Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea, which I think is an extraordinary work of the imagination, which fleshes out the first Mrs Rochester and gives us an entirely different view of this so-called madwoman in the attic. But I still always loved Jane Eyre as a piece of literature.”

Jane Eyre was the novel that ensured Charlotte Brontë became a popular sensation. After her death, memorabilia became increasingly sought after and valuable, and the idea of literary reputation forms part of Devlin’s narrative. It is told by Mary — the young woman who greets Charlotte in Dublin — who eventually marries her widower, Arthur, the relative she has known since her parents fostered him and his brother.

Mary knows that Charlotte is Arthur’s first love, but provides a stable and loving home for him in Offaly. It is when she herself is widowed and facing increasingly straitened circumstances that she begins to sell off Charlotte’s possessions and effects, which Arthur had transported back from Haworth Parsonage.

There were many. When Arthur left Haworth, Devlin describes “a kind of yard sale, and villagers were buying saucepans, everything, all sorts. He had the bed, the marital bed — the bed that Charlotte died in — chopped up and buried. He didn’t want anyone getting their hands on that.”

Read more

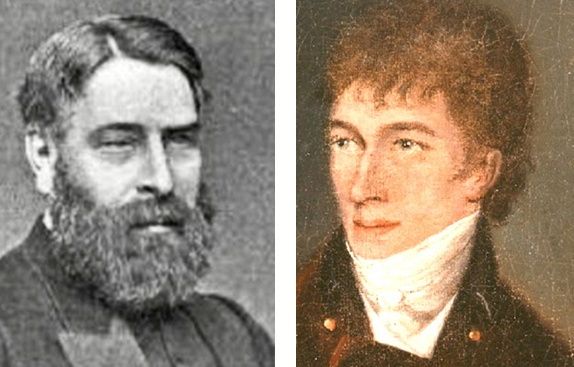

A wedding against her father’s wishes: Charlotte’s husband Arthur Bell Nicholls (left); and her father Patrick Brontë

Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography had only strengthened the craze for all things Brontë, and the three sisters were together seen as tragic geniuses living in rural isolation in Yorkshire, each destined to die prematurely. The Victorian obsession with commemorating death can only have fed into the myth — when, in fact, much of their lives were more prosaic.

Devlin describes the immense effort that Charlotte made to ensure that her father and her husband were able to co-habit peaceably in Haworth Parsonage: “Anne, on her death-bed apparently, had said to Charlotte, ‘take courage’, and Charlotte showed great courage and determination in making this marriage happen against her father’s wishes,” she explains.

The night before her wedding, her father told her that he was not going to give her away. “She was devastated, but she had very good friends, and two of them were there at the wedding, Ellen Nussey and Margaret Wooler, who was retired at this stage, but had been Charlotte’s teacher among the schools she attended. And she said, ‘Well, let’s check the Book of Common Prayer and see’. She realised it didn’t have to be a man who gave a woman in marriage, and so she stood for her.”

‘I feel that Ireland had a stronger pull on her imagination than has necessarily been acknowledged’

Charlotte, who wrote her novels at the dining-room table, arranged for both men to have a study, having an old boot-room knocked through, plastered and painted for Arthur.

Devlin is fascinated by the enthusiasm with which Brontë entered into marriage, carefully assembling her trousseau and almost willing herself to feel love for her new husband: “She was under no illusions about her looks. She was not a beautiful woman, at a time when a woman’s looks were her currency. She was 38 when she married, and had lost some of her teeth. The well-known image of her is a very romantic image; the most credible representation of her is the one done by her brother Branwell, the ‘pillar portrait’ in the National Gallery in London. You’ve got a square face, and really a shoehorn of a nose. Against that, she had fine eyes and lovely soft hair, and she was very elegant, very particular about her appearance.”

One of the questions that remains alive for Devlin is whether Brontë would have written about Ireland, given that she used so much of her life in her fiction. She is intrigued by the theory that Patrick Brunty had a bardic ancestor, and connects some of the gothic elements of the sisters’ works, and Wuthering Heights in particular, with Irish storytelling traditions. Of Charlotte, she says, “I feel that Ireland had a stronger pull on her imagination than has necessarily been acknowledged.”

1854 visit: One of the last remaining buildings at Cuba Court, where Charlotte Brontë spent her honeymoon, and inset, how the house once looked

Devlin has frequently looked to the past for inspiration in writing her own novels, which include Edith, based on the life of one half of Somerville and Ross, authors of The Irish RM, The House Where it Happened, inspired by an 18th-century Irish witchcraft trial, and Ship of Dreams, in which she drew on a family story to explore the passengers on the Titanic.

It’s a marked contrast to her other career as a journalist and a columnist. Does she think she needs the pull of contemporary life to complement her fictional forays into the past? “It takes a couple of years to write a novel, at least,” she smiles, “and you still have to pay bills, so it’s useful from that point of view. But also it keeps me in the world a bit.”

She has some captivating stories from her time in journalism, particularly interviews with the famous and the notorious. Actress Shirley MacLaine once admired her suit, and Chubby Checker taught her to do the twist in his hotel suite — apparently the trick is to pretend you’ve just got out of the shower and you’re drying yourself with a towel.

But the most hair-raising is her trip to Parkhurst maximum security prison to meet gangster Reggie Kray: “He picked me up off the ground by my elbows, and planted this kiss on my mouth. And it must have lasted for quite a long time, because I remember just dangling there, thinking, ‘I’m being kissed by a gangland killer and there’s nothing I can do about it’.”

Kray wrote to her repeatedly after their meeting, asking her to send a photograph of herself and enter into a correspondence. Sensibly, she did not, and it seems unlikely that this encounter will form the basis of another novel. But for Devlin’s fertile imagination, there are bound to be other stories to tell.

Charlotte: A Novel by Martina Devlin

‘Charlotte: A Novel’ by Martina Devlin (Lilliput Press) is out now