If the polls and social media are to be believed, the Rupert Lowe controversy has brought Reform UK’s astonishing rise to an end.

The insurgent party’s support has dipped from 25 per cent to 23 per cent, putting them in second place behind Labour, while the Tories gained a one-point boost to put Kemi Badenoch’s party in third place on 22 per cent.

While it’s easy to get caught up in the melodrama, data suggests that Reform will not only ride out this storm – it is well positioned to seize power in the coming years as the party reflects the country’s direction of travel.

Reform UK stands to benefit from the rise in “Englishness”, data suggests

Getty Images/ P Whiteley, CC BY-ND

How?

Farage – arguably better than any other politician in living memory – has tapped into a deep well of “Englishness” that appears to be on the march.

Surging English nationalism has disrupted British politics in recent years, with Brexit being the most obvious manifestation.

The close relationship between English identity and Euroscepticism partly led to this political spasm.

In 2019, Boris Johnson’s campaign to ‘Get Brexit Done’ was propelled by a deeply felt sense that Englishness had been betrayed as Parliament “thwarted the will of the people”. He went on to win an 80-seat majority that year.

As elections guru John Curtice previously told GB News, voting patterns have barely shifted since 2019.

It’s also worth noting the role devolution anxiety played in that election. The fear of a Labour tie-up with the Scottish National Party (SNP) played a key role in the Conservative Party’s successful campaign against Jeremy Corbyn.

This rise in Englishness is borne out in the research. Professor Richard Wyn Jones of Cardiff University’s Wales Governance Centre and Professor Ailsa Henderson of the University of Edinburgh spent 10 years exploring political attitudes in England through their Future of England Survey, the most detailed study of attitudes in England towards national identity and constitutional change.

The nine big quantitative surveys of “Englishness” they have conducted since 2011 demonstrate that the number of people who describe themselves as exclusively or mainly English rather than British is growing, and that the notion of “Britishness”— is splintering.

How does this benefit Reform?

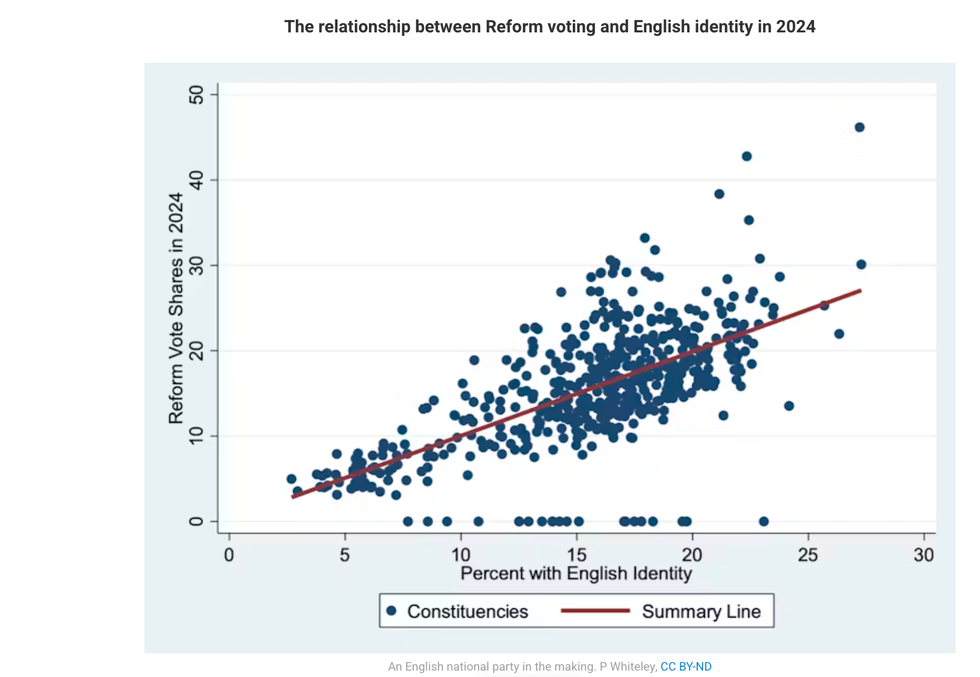

Professor Paul Whiteley of the University of Essex recently compared the percentage of Reform voters with those who identified as English in the 2021 census in England.

LATEST MEMBERSHIP DEVELOPMENTS

The more English identifiers there are in a constituency, the greater support for Reform.

Getty Images/ P Whiteley, CC BY-ND

He found a strong relationship between the two measures (see chart above). The more English identifiers there are in a constituency, the greater support for Reform. In effect, Reform has become an English national party.

This rise of “Englishness” at the expense of “Britishness” over time could therefore reinforce support for Reform.

As Curtice points out, nationalistic fervour can propel insurgent parties to power. A recent case study can be found north of the border.

Though Scotland voted 55 per cent to 45 per cent to remain in the UK, the 2014 referendum energised the pro-independence movement. SNP membership subsequently surged, making it the dominant force in Scotland.

The SNP then destroyed the traditional two-party system destroyed in 2015.

Before that seismic election, the SNP were the third party behind Labour and the Conservatives in Scotland.

The party’s gains came largely at the expense of Labour, as many voters who supported Scottish independence tactically voted for the SNP to ensure that Scotland would have a significant say in Westminster, fearing a Conservative majority.

A similar path to power could open up for Reform, Curtice adds.