The expanding waistbands of the English public have left the nation lagging behind other European countries when it comes to life expectancy, a study suggests.

Experts have called for urgent action to help people get healthier, with poor diets and coach potato lifestyles partly to blame, researchers suggested.

Advances in life expectancy between 1990 and 2011 have been attributed to improvements in heart disease and cancer care.

But poor diets, low levels of exercise and increasing body mass index (BMI) scores have been linked to the slow down of these improvements in 2011 to 2019.

Academics wanted to assess life expectancy advances across 20 European countries from 1990 to 2021.

Researchers, led by experts from the University of East Anglia (UEA), compared several factors linked to life expectancy across England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden.

All countries showed annual improvements in life expectancy in 1990 to 2011, with an overall increase of an average of 0.23 years.

The rate of improvement was lower in 2011–19 than in 1990–2011 in all countries except for Norway.

We need your consent to load this Social Media content. We use a number of different Social Media outlets to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity.

From 1990 to 2011, life expectancy in England rose by an average of 0.25 years.

This slowed to an average increase of 0.07 years in 2011 to 2019.

Researchers said that England experienced the largest decline in life expectancy improvement during the period studied.

Between 2019 and 2021, which includes the first part of the Covid-19 pandemic, most countries saw a fall in life expectancy except for Ireland, Iceland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.

(PA Graphics)

Researchers said that the countries which “best maintained” improvements in life expectancy had fewer heart disease and cancer deaths.

They called for government action to improve overall population health, including helping people have better diets and more exercise.

Lead researcher Professor Nick Steel, from UEA’s Norwich Medical School, said: “Advances in public health and medicine in the 20th century meant that life expectancy in Europe improved year after year, but this is no longer the case.

“We found that deaths from cardiovascular diseases were the primary driver of the reduction in life expectancy improvements between 2011–19. Unsurprisingly, the Covid pandemic was responsible for decreases in life expectancy seen between 2019–21.”

He continued: “Countries like Norway, Iceland, Sweden, Denmark, and Belgium held onto better life expectancy after 2011, and saw reduced harms from major risks for heart disease, helped by government policies.

“In contrast, England and the other UK nations fared worst after 2011 and also during the Covid pandemic, and experienced some of the highest risks for heart disease and cancer, including poor diets.”

Asked about England specifically, he told the PA news agency: “We’re not doing so well with heart disease and cancer.

“We have high dietary risks in England and high levels of physical inactivity and high obesity levels.

“These trends are decades long – there isn’t a quick fix.

“And I guess the message to the current Government is, ‘Great that one of your big three shifts for the NHS is to move to prevention, but it needs to be more than … easy access to scanners and a well man check or well woman check with your already overloaded GP.

“This is about the big, long-term population protections from risk – so engaging with the food industry to improve our national diet to make it easier for people to eat healthier food and make it easier for people to move a little bit in our day-to-day lives.”

But he said that we have “not yet reached a natural longevity ceiling”.

Prof Steel added: “Life expectancy for older people in many countries is still improving, showing that we have not yet reached a natural longevity ceiling.

“Life expectancy mainly reflects mortality at younger ages, where we have lots of scope for reducing harmful risks and preventing early deaths.

“Comparing countries, national policies that improved population health were linked to better resilience to future shocks.”

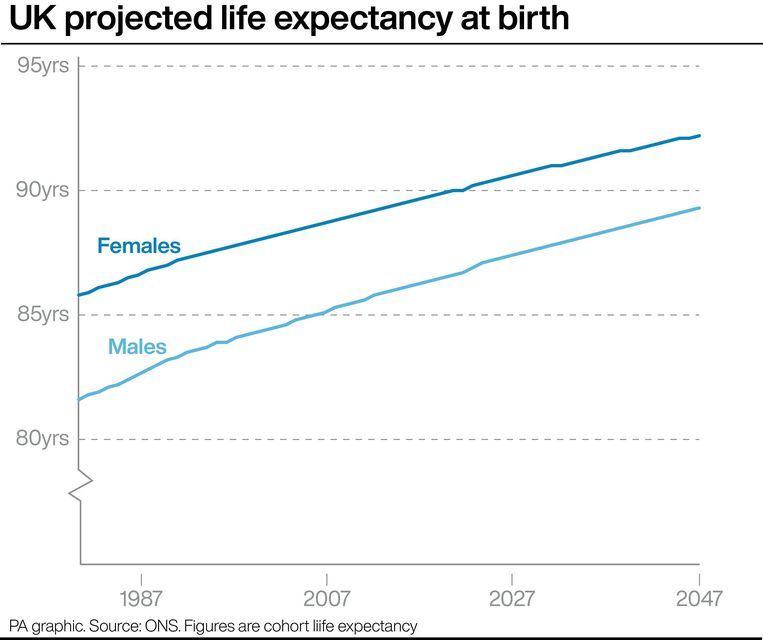

Figures from the Office for National Statistics released last week show that about one in five girls born in the UK in 2030 is projected to live on average to at least 100 years old, rising to almost one in four by 2047.

The projections are lower for boys, but still indicate a rise, with more than one in eight males born in 2030 living to celebrate their centenary, climbing to about one in six by 2047.