Medics have performed a UK-first operation to remove a type of head cancer using keyhole surgery through a patient’s eye socket.

Mother-of-three Ruvimbo Kaviya had a meningioma removed from the space located beneath the brain and behind the eyes.

Many of these types of tumour would have previously been considered inoperable because of where they are situated in a area called the cavernous sinus.

And those which have been removed required complex surgery which involves taking off a large part of the skull and moving the brain to access the tumour – which in itself can lead to serious complications including seizures.

But now surgeons from Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust managed to remove one of these tumours using keyhole surgery through Ms Kaviya’s eye socket – the first surgery of its kind in the UK.

A small scar at the corner of Ruvimbo Kaviya’s eye after she received the surgery (Danny Lawson/PA)

Experts at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust practised the surgery multiple times – first using 3D models of Ms Kaviya’s head and then in a cadaver lab.

The surgery, known as a endoscopic trans-orbital approach, took just three hours and Ms Kaviya, a nurse in Leeds, was up and walking about later the same day.

She has been left with a tiny scar near her left eye.

Surgeons have now performed similar surgeries, giving hope to UK patients whose cancers were previously seen as inoperable.

Neurosurgeon Mr Asim Sheikh, told the PA news agency: “There’s been a move towards minimally invasive techniques over the last few years or so, with the advancement of technology, tools, 3D innovation, it is now possible to do the procedures with less morbidity, and that means the patients recover quicker and better.”

He said traditional methods to get to the place where the tumour was situated requires “pressing on quite a lot of brain”.

“So if you press on it too much, or retract it, or try and move it apart, then it can lead to patients having seizures afterwards,” Mr Sheikh said.

“Whereas this way, we’re not even sort of touching the brain.

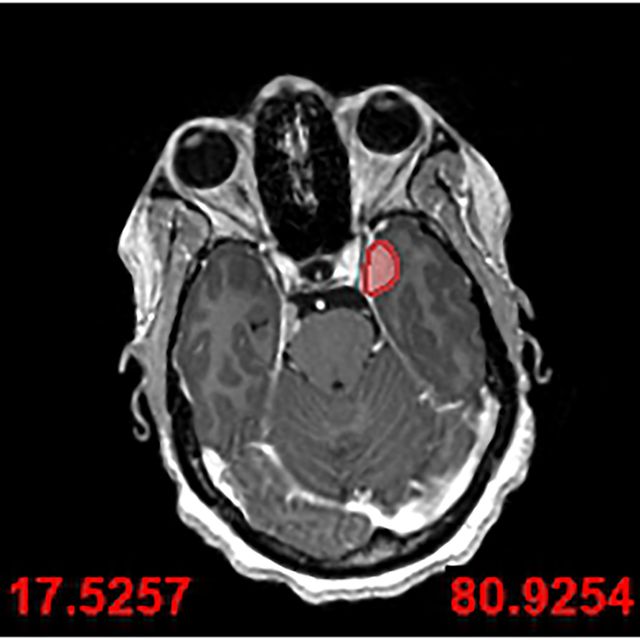

An MRI scan used by surgeons to visualise Ruvimbo Kaviya’s tumour (Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust/PA)

“It’s a hard to reach area, and this allows a direct access without any compromise of pressure on the brain.

“So it just reaches us in areas which are once thought to be inoperable, but now are accessible.”

His colleague Mr Jiten Parmar, a maxillofacial surgeon, devised a technique where a little part of the outside wall of the eye socket was cut to allow more access for the endoscope.

“We innovated a new technique, which I think is unique to Leeds, to make the operation much easier,” Mr Parmar said.

He said that before this new keyhole technique, the area that needed to be operated on is “difficult to get to from the outside without taking off most of the skull plate” which in itself can cause some quite serious damage.

“Going through the eye socket gets into the same area and it’s a way more elegant approach,” he told PA.

“It reduces the morbidity for the patient because you disturb your blood vessels and fewer nerves.”

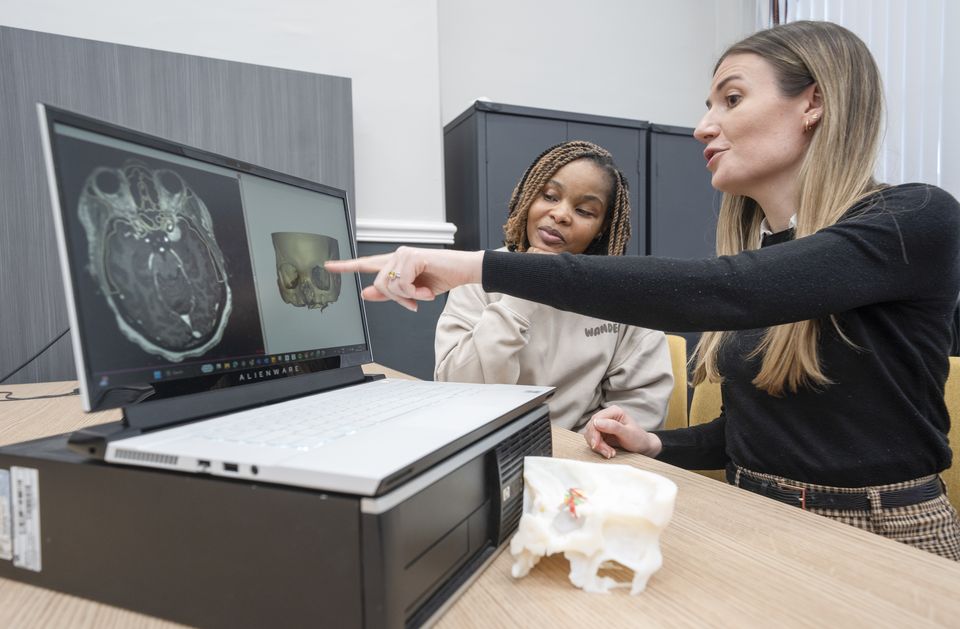

Lisa Ferrie, biomedical engineer and head of the 3D planning service at Leeds, made a 3D model of the patient’s skull so the surgical team could rehearse the operation before they did it.

(l to r) Ruvimbo Kaviya and biomedical engineer Lisa Ferrie look at an MRI scan and 3D digital model of the tumour (Danny Lawson/PA)

Ms Ferrie added: “When the surgical team approached me, we used scans of Ruvimbo’s brain and skull to create a 3D replica model.

“This technology enabled the team to study her anatomy in detail and prepare for the procedure with unparalleled accuracy. Seeing the model and knowing it contributed to this groundbreaking surgery is incredibly rewarding.”

Mr Parmar added: “It was so well rehearsed, it felt like we’d done it 100 times before – and that’s the way it should be when using a new technique.

“And actually, when we did that, we actually got a brilliant result.”

Mr James Robins, fellow in neurosurgery, added: “This is major surgery through minimally invasive techniques – so it’s still a massive surgery.

“Using the endoscope, it’s about five millimetres in diameter, we only need a very small space in order to gently displace the eye to one side to get to the back of the eye socket, removing a small, tailored amount of bone.

“And that’s where Lisa comes in. She enables us to model this patient’s skull beforehand to tell us exactly how much bone we can remove, and then we can remove the precise amount of bone, and then we can remove the tumour, usually from inside out, and just gently, down for a small operative corridor. That’s how we did it.”

Ms Kaviya said that she did not even think about being the first UK patient to undergo such a procedure because the tumour was causing such severe headaches.

Ruvimbo Kaviya after surgery (Ruvimbo Kaviya/PA)

“I had some headaches which felt like an electric shock on my face,” she told PA.

“I couldn’t even touch my skin on the face, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t brush my teeth, it was really terrible.”

She was eventually diagnosed with a meningioma in 2023 which medics said they would monitor.

During monitoring a second meningioma was also found in October that year.

Medics at Leeds consulted experts in Spain who said that she would be a good candidate for this new surgery and the operation was performed in February 2024.

The 40-year-old nurse needed three months off work after the surgery but is now back caring for patients needing stroke rehabilitation in Leeds.

“It was a really tough time, I was told I had one tumour and then told I had another, I don’t know how I managed to cope,” she said.

“It was very stressful and difficult.

(l to r) Consultant neurosurgeon Asim Sheikh, Ruvimbo Kaviya, biomedical engineer Lisa Ferrie and facial surgeon Jiten Parmar (Danny Lawson/PA)

“So when they told me that they’re going to do the surgery – they couldn’t say that it was going to be perfect and there was risk involved.

“It was the first time they were doing the procedure. I had no option to agree because the pain was just too much – I didn’t even think about it being the first time, all I needed was for it to be removed.”

Ms Kaviya, whose three children are aged eight, 12 and 13, said her family were “sceptical” about the procedure, adding: “But I just, I just told them that ‘I just have to do this – it’s either I do it or it, it keeps growing, and maybe I will die. Who knows?

“There’s a first time to everything. So you never know, this might be the best chance for me to have it’. And it was.”

On her recovery she added: “When I had the operation I thought I was possibly going to stay in the hospital for weeks or months and I was home in days.

“I had double vision for about three months but everything else was OK.”

She said that she put herself in the place of her patients to help herself through recovery and has been left with a “really tiny” scar.

She added: “If you don’t really look closely, you won’t be able to see.”