The Cambridge spy Kim Philby declared he would have done it all again after he finally confessed that he had been for years a Russian agent, according to newly-declassified intelligence files.

The dramatic moment in January 1963 when he owned up to his treachery after being confronted by his oldest friend, and fellow MI6 officer Nicholas Elliott, is vividly captured in a transcript of their conversation released to the National Archives in Kew, west London.

But while Philby admitted that he had been working for the Soviets since the 1930s, his confession is littered with lies and evasions – including a false claim that he had broken off contacts with the KGB in 1946 after the Second World War.

In fact, he had never stopped working for the KGB and shortly after the encounter with his old friend in the Lebanese capital, Beirut, he quietly slipped away on a Russian steamer eventually resurfacing in Moscow.

For years, Philby had been a high-flying MI6 officer tipped as a future chief of the service – C – only to be forced to quit after coming under suspicion when his two fellow Cambridge spies, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, fled to Russia in 1951.

In 1956, however, he had been quietly readmitted after MI5, the security service, was unable to prove his guilt, and moved to Beirut under the cover of being the Middle East correspondent of The Observer.

By 1963, fresh evidence had emerged, and C, Sir Dick White, dispatched Elliott to confront him, despite the objections of some in MI5, who believed he would be too soft on his old friend.

After one inconclusive meeting at an MI6 flat – where Elliott told Philby he had seen new information which had finally convinced him of Philby’s treachery – they met for a second time on January 9, with MI6 secretly recording their words.

According to the transcript, Philby immediately, declared he was ready to open up, telling Elliot: “I think Dick White’s psychology on this occasion has proved good.

“I certainly would not have spoken to anyone else and when you yourself told me that you believed the evidence against me, that really did it. Here’s the scoop as it were.

“I have had this particular moment in mind for 28 years almost, that conclusive proof would come out.

“The choice actually is between suicide and prosecution. This is not in any sense blackmail, but a statement of the alternatives before me.”

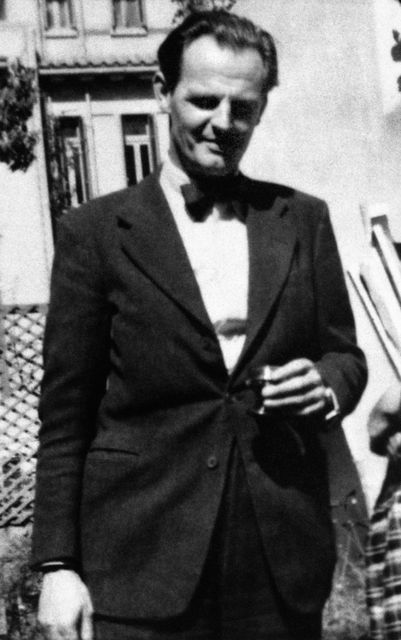

Donald Maclean was tipped off by Philby that he was about to be unmasked (PA)

In the course of the interview, he admitted he had betrayed Konstantin Volkov – a KGB officer who tried to defect to the West bringing with him details of traitors operating in British intelligence and the Foreign Office, which would have inevitably led to Philby’s exposure.

Instead, as a result of Philby’s intervention, he was abducted by the Russians in Istanbul, drugged, taken back to Moscow and executed.

Philby acknowledged that he had tipped off Maclean, whom he had recruited in the 1930s, that he was about to be arrested – “the least thing I could do was to get him off the hook” – but said Elliott could give White his word that he had had no other contacts with the Russians since 1946.

He claimed that his change of heart had been due to the advent of Clement Attlee’s Labour government, which had brought in many of the things he believed in, and that confessing had been a “tremendous relief”.

“I am beginning to understand Catholics and all that,” he said.

“The only major doubt actually I had in my mind is ought I … in 1946 having broken off contact, to spill the whole beans and I very nearly did and I thought to myself, ‘Oh to hell with it, why should I?’”

He described his life in MI6 as a time of “controlled schizophrenia”.

“I really did feel a tremendous loyalty to MI6, I was treated very, very well in it and I made some really marvellous friends there. But the over-ruling inspiration was the other side,” he said.

As the meeting drew to a close, Elliott recalled a conversation they had once had when Philby had said that he always considered loyalty to friends more important than loyalty to country.

He said that it was clear from Philby’s comment that in practice “idealism could bitch the friends”. Philby agreed adding that “if he had his whole life to lead again, he would probably have behaved in the same way.”

Two days later they met for a third time when Philby handed over a six-page typewritten account of his recruitment and work for the Russians.

Elliott quizzed him about other suspected Soviet agents, including his fellow Cambridge spy Anthony Blunt, however, Philby insisted that in his view “Blunt did not, and would not, have worked for the Russians” although he had “no hard information”.

The file also includes a letter, intercepted by MI5, which Philby wrote to his wife, Eleanor, following his flight from Beirut when his whereabouts were still unknown.

Addressing her as “my beloved”, he said that he been “called away at short notice” and had left some Lebanese pounds for her in the “big Latin dictionary” among his father’s books.

“I am sorry I cannot be more explicit at the moment but my plans are somewhat vague. Don’t worry about anything. We will meet again soon. Tell everyone that I am doing a tour of the area,” he wrote.

In a PS, he added: “Please destroy this as soon as your have found the cash.”