Irish officials were worried about the potential reaction of the Government to a decision not to prosecute INLA paramilitary Dessie O’Hare, nicknamed the Border Fox, for the attempted murder of a prison officer in Northern Ireland.

Confidential files released as part of the State Papers by the National Archive revealed the government in the Republic was deeply concerned about how a decision by the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) would be perceived in London.

The papers, from June 27, 1980, included correspondence between then Irish justice minister Gerry Collins and taoiseach Charles Haughey over the potential implications of the decision.

Irish government fears focused on whether the decision might instigate retaliation by loyalist paramilitaries and result in “bombs in border towns on our side or in Dublin”.

The DPP decided not to prosecute O’Hare for the attempted murder of a prison officer in Armagh in 1979.

Northern Ireland authorities had raised concerns about delays in the operation of the Criminal Law (Jurisdiction) Act 1976, under which someone could be prosecuted in the Republic for alleged offences committed across the border.

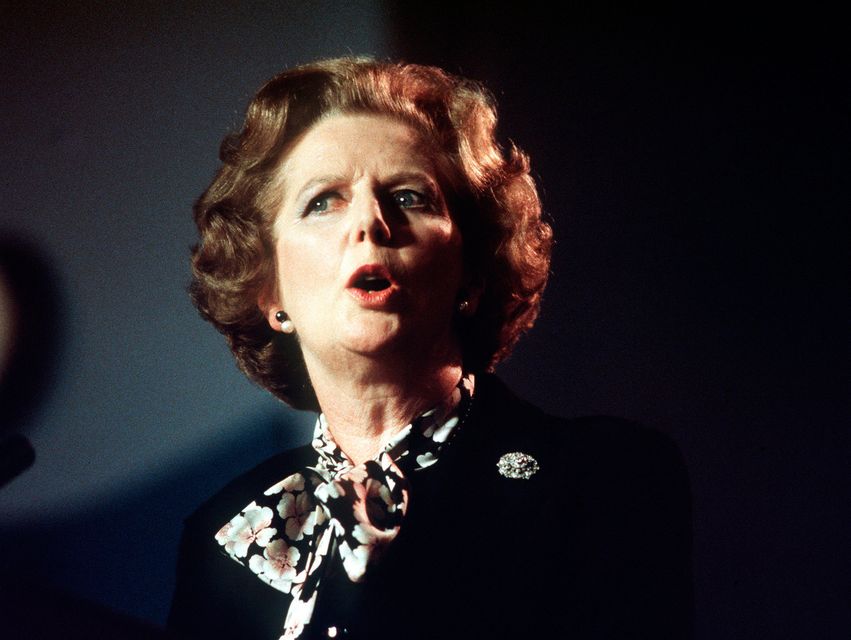

Then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had expressed her anger to the Irish authorities over not using the legislation to prosecute O’Hare.

The incident arose after an Army foot patrol came under fire in Keady, Co Armagh, on June 9, 1979. A short time later, the attackers hijacked a lorry in an attempt to escape the gun battle.

As they were fleeing to the border in the lorry, the three paramilitaries involved in the attack – O’Hare, Eugene McNamee and Peadar McElvanna – opened fire on an off-duty prison officer outside his home.

The officer returned fire and fatally wounded McElvanna. A short time later, another vehicle dropped O’Hare and McNamee, who had both suffered gunshot wounds, and the body of McElvanna at Monaghan Hospital.

Former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher. Photo: PA

In his letter to the taoiseach, Mr Collins said gardaí had submitted a file to the DPP in August 1979 and there had been a general belief among An Garda Síochána and the RUC that adequate evidence was available to charge O’Hare and McNamee.

Mr Collins was made aware on March 28, 1980 by the then attorney general Anthony Hederman that a decision had been taken not to prosecute either man.

Mr Collins said he was obliged to accept the decisions of the DPP and attorney general, but said it was important that “clear and speedy decisions should be communicated with explanation of the legal reasons”.

He pointed out there had been recent demonstrations by loyalists, as well as calls by unionist leaders Ian Paisley and Jim Molyneaux for the mining of cross-border roads in response to a spate of murders in south Fermanagh.

Unless there was communication about decisions, the minister expressed fear that there could be “retaliatory” action from certain groups in Northern Ireland who might regard a decision not to prosecute as indicating “a lack of willingness on the part of the authorities here to deal with seriously flagrant breaches of the law”.

“It could indeed result in bombs in border towns on our side or in Dublin,” Mr Collins said.

The DPP and attorney general were against preferring charges against O’Hare and McNamee, though they originally believed the evidence would support a charge of attempted murder.

Mr Hederman explained to the justice minister that a study of photos and a map of the area around the prison officer’s home had “altered the entire complexion of the case”.

The attorney general said it was clear from such evidence that the account given by the prison officer in a statement to the RUC could not be correct, which meant the proposed charges of attempted murder and intent to endanger life against O’Hare and McNamee would be “virtually unstateable”.

Mr Hederman said he and the DPP were in agreement on the issue, but they believed the evidence would support charges of possession of firearms against both men. However, he said they did not believe it would be in the public interest to prefer such charges.

Mr Hederman informed the UK attorney general Michael Havers of the decision not to prosecute O’Hare in August 1980. Documents now declassified show officials telling their Irish counterparts how it was difficult to understand how neither O’Hare nor McNamee had been arrested, interrogated and charged.

One diplomat with the British embassy in Dublin said officials were “outraged by the inadequacy of the action taken”.