As preparations were being made to entomb former Syrian president Hafez al-Assad in a mausoleum nearby, a young Imam sat on the steps of the mosque and sighed, before confessing a dangerous theological and political truth.

“As Alawites, we’re not Shi’a Muslim, you know? We’re not strictly speaking very Muslim, really. Under Assad we just subscribed to all that to create a power block with Shi’a in Lebanon and in Iran to support our minority rule.

“We see all men of genius — Jesus, Plato, even Shakespeare — as manifestations of the divine. We’re not lying about being Muslim, but we’re also theologically Christian, and Jews,” he explained 24 years ago in the mountain village of al-Qardahah.

Syria’s Alawites kept that quiet.

People gather on Sunday in Istanbul to celebrate the Syrian government’s fall (AP Photo/Emrah Gurel)

For decades Hafez, and then his son Bashar, saw being part of a “Shi’a crescent” that tied them to Tehran and Lebanon as their best means of survival. Many Christians fell in with them out of fear of the Sunni majority.

As Syria collapsed into civil war in 2012 Bashar and the dictator’s henchmen did everything they could to increase the sectarian rivalries that had always threatened to tear the country apart.

They figured they’d survive longer if they emptied their prisons of Islamist political detainees, let the Kurds do their own thing, and murdered the rest with help from Iran and Russia.

No matter that this led to the emergence of the so-called Islamic State in eastern Syria with its harvest of blood and horror, a secession of Kurds (who then got attacked by Turkey) and the gangsterisation of the whole country, the Assads survived another dozen years.

But with Russia distracted in Ukraine and Hezbollah hammered by Israeli airstrikes, Syria’s Sunni Islamist-led opposition has swept the Assads away in less than a week.

No wonder Syrian minorities, especially Alawite and Christian, are celebrating the end of dictatorship by joining in with shouts of “One Syria. One Nation. We are One People!” as loud as they can.

Now’s not the time to highlight your difference if you’re different in Syria.

Syria’s tragedy is that it’s not one nation and that almost none of its neighbours see any advantage in it emerging from the death of the Assad regime as anything other than a mess.

Israel doesn’t want a stable Syria, as the Jewish state has occupied the Syrian Golan Heights since 1967, and captured more in 1973.

It won’t ever allow Damascus to return to the eastern banks of the Sea of Galilee.

An opposition fighter steps on a broken bust of the late Syrian president Hafez Assad in Damascus (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan might want to see the back of the more than 3m Syrian refugees his country has absorbed, but he also wants free rein to attack Kurdish groups on Syrian territory.

He’s been backing Syrian militia who continue to do that right now.

He would not be able to do so if Syria settled down into a democracy.

He might, however, back Sunni Islamist parties if they seize power in return for a joint operation against the Kurd-ruled Syrian region of Rojava.

Iran may have lost its proxy in the House of Assad, but its other Hezbollah puppets in Lebanon and in Iraq will continue to destabilise Syria, just as they have in Iraq, to prevent Sunni hegemony.

And, of course, parts of an unstable Syria would be useful for Iranian groups to attack Israel, which means that Lebanon’s Hezbollah will continue to keep the country off balance.

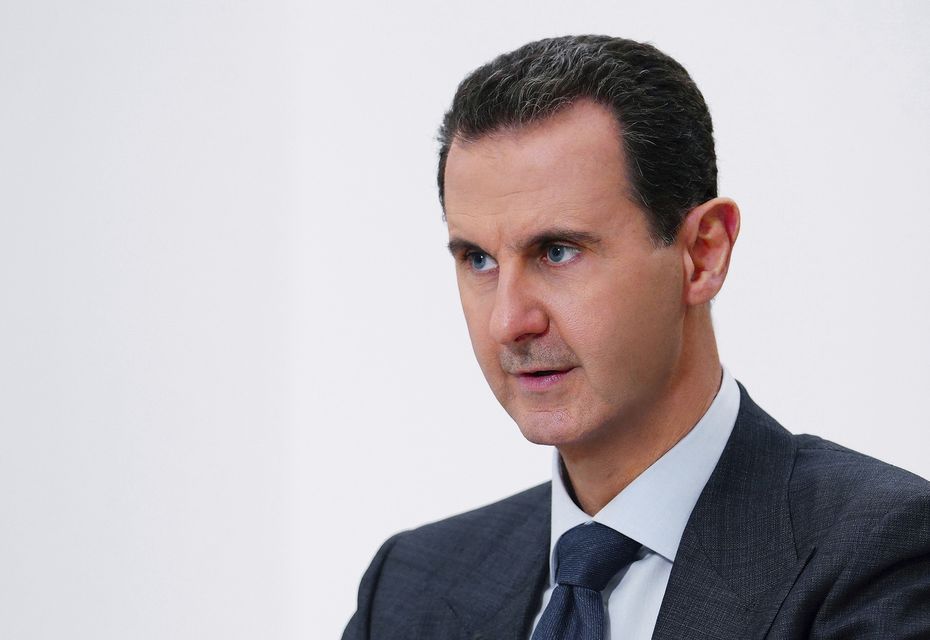

Former Syrian president Bashar Assad (SANA via AP)

The drive against Assad has been led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham under Abu Mohammed al-Golani.

His movement began life as a branch of Islamic State and al-Qaida but formally split from the latter in 2016.

It has carefully cultivated its political image, won plaudits for its administration of areas under its control and reached out to protect minorities.

As the likely head of a transitional administration in Syria’s fractured hydra-headed rebel movement, al-Golani may try to stick to a moderate political agenda.

But this will be a struggle. Chaos in Syria from an Israeli, Turkish, Iranian and Shi’a perspective would be better than stability and a steady transition to, of all things, democracy. Chaos is much easier to achieve.

“The future is ours,” al-Golani said as he led celebrations in Damascus on Sunday.

Who he means by that is not yet clear.

But uniting a whole country which will be getting a lot of help to continue to tear itself apart… that will take the kind of genius the Alawite Imam in Assad’s home town said was evidence of the divine.

Sam Kiley has been covering the Middle East for 35 years.