France’s far-right and left-wing forces are expected to join together on Wednesday to oust Prime Minister Michel Barnier’s government in a historic no-confidence vote prompted by budget disputes.

If the motion succeeds, it would mark the first time a French government has been toppled this way in more than 60 years.

President Emmanuel Macron insisted he will serve the rest of his term until 2027 despite growing opposition calls for his departure amid the turmoil.

However, Mr Macron will need to appoint a new prime minister for the second time after his party’s losses in July’s legislative elections.

Far-right leader Marine Le Pen delivers her speech at the National Assembly prior to a no-confidence vote that could bring down the government (AP Photo/Michel Euler)

Mr Macron, on his way back from a presidential visit to Saudi Arabia, said discussions about him potentially resigning were “make-believe politics”, according to French media reports.

“I’m here because I’ve been elected twice by the French people,” Mr Macron said. He was also reported as saying: “We must not scare people with such things. We have a strong economy.”

The no-confidence motion rose from fierce opposition to Mr Barnier’s proposed budget.

The National Assembly, France’s lower house of parliament, is deeply fractured, with no single party holding a majority.

It comprises three major blocs: Macron’s centrist allies; the left-wing coalition New Popular Front; and the far-right National Rally.

Both opposition blocs, typically at odds, are uniting against Mr Barnier, accusing him of imposing austerity measures and failing to address citizens’ needs.

Mr Barnier, a conservative appointed in September, could become the country’s shortest-serving prime minister in France’s modern Republic.

In last-minute efforts to try to save his government, Mr Barnier called on lawmakers to act with “responsibility” and think of “the country’s best interest”.

“The situation is very difficult economically, socially, fiscally and financially,” he said, speaking on national television TF1 and France 2 on Tuesday evening.

“If the no-confidence motion passes, everything will be more difficult and everything will be more serious.”

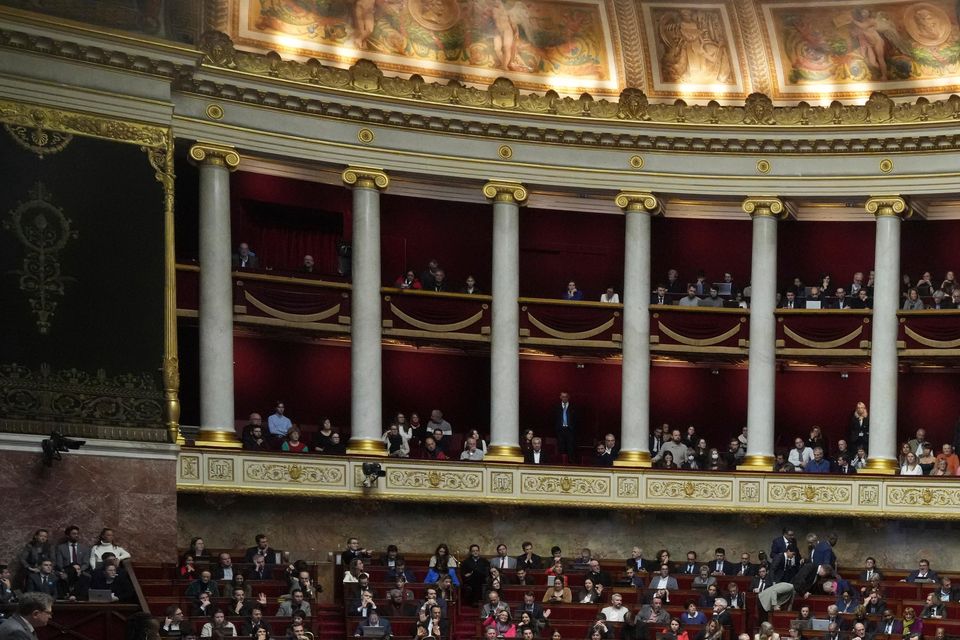

Lawmakers convene at the National Assembly in Paris during a debate and prior to a no-confidence vote (AP Photo/Michel Euler)

Speaking at the National Assembly ahead of the vote, National Rally leader Marine Le Pen, whose party’s goodwill was crucial to keeping Mr Barnier in power, said “we’ve reached the moment of truth, a parliamentary moment unseen since 1962, which will likely seal the end of a short-lived government”.

“Stop pretending the lights will go out,” hard-left lawmaker Eric Coquerel said, noting the possibility of an emergency law to levy taxes from January 1, based on this year’s rules.

“The special law will prevent a shutdown. It will allow us to get through the end of the year by delaying the budget by a few weeks.”

The National Assembly said the no-confidence motion requires at least 288 of 574 votes to pass. The left and the far right count over 330 lawmakers — yet some may abstain from voting.

If Mr Barnier’s government falls, Mr Macron must appoint a new prime minister, but the fragmented parliament remains unchanged.

No new legislative elections can be held until at least July, creating a potential stalemate for policymakers.

While France is not at risk of a US-style government shutdown, political instability could spook financial markets.

France is under pressure from the European Union to reduce its colossal debt.

The country’s deficit is estimated to reach 6% of gross domestic product this year and analysts say it could rise to 7% next year without drastic adjustments.

The political instability could push up French interest rates, digging the debt even further.