Concerns have been raised about the care and support people receive while facing long waits in A&E.

A major new survey has found that many emergency care patients felt they were not able to get help with their condition while waiting.

And more than a quarter said they were given no pain relief while in the queue to see a medic.

The survey results have prompted concerns about patient experience as the NHS heads into winter, which is traditionally a busy time for emergency and urgent care services.

(PA Graphics)

The health watchdog, the Care Quality Commission (CQC), published the results of a survey of 45,500 people who used NHS urgent and emergency care services (UEC) in England this year.

The CQC said that the “stream of demand” for care is driving lengthy waits for some and causing “difficultly for some patients in accessing information, emotional support and adequate pain relief”.

The survey found:

– Among A&E patients, 60% said they felt that doctors or nurses “completely” explained their condition or treatment to them in a way that they could understand, more than a quarter (28%) said this only happened “to some extent” and 11% said it did not happen at all.

– Of the 27% of survey respondents who arrived at A&E by ambulance, 61% said they were handed over to A&E staff within 15 minutes, but 17% reported waiting more than an hour.

– More than a quarter (28%) of patients treated at a major A&E centre responding to the survey said they waited for more than an hour to be assessed by a nurse or doctor after arriving at A&E and 47% said they were not able to get help with their condition or symptoms while waiting.

– Almost two thirds (64%) of patients said they waited more than four hours to be admitted, transferred or discharged at A&E.

– For people who needed help with medications for a pre-existing medical condition while in the department, more than a quarter of urgent treatment centre (UTC) respondents (26%) and a similar proportion of A&E respondents (28%) said they did not receive that help.

– Less than half of people attending either an A&E (42%) or an urgent treatment centre (47%) who needed help with pain relief thought that staff “definitely” helped them control their pain. And more than a quarter in both services said they were not given any help with pain relief – 27% in A&E and 26% in an urgent treatment centre.

The CQC said that the results also show “scope for improvements in discharge” after a third of patients seen in A&E said they were not given information on how to care for their condition at home.

One in five (21%) of people discharged from an A&E department said that they were not told who to contact if they were worried about their condition or treatment after leaving A&E.

Meanwhile, almost a third (31%) of A&E patients and nearly a quarter (23%) of UTC patients who felt they needed to have a conversation with staff about further health or social care after leaving hospital said the mater was not discussed with them.

The CQC said that the responses also indicate that not being able to get a GP appointment quickly enough and wanting to be seen on the same day were both factors directly influencing people’s decisions to seek treatment at a UEC service.

Chris Dzikiti, the CQC’s interim chief inspector of healthcare, said: “Urgent and emergency care services nationally continue to be under intense pressure – something reflected in recent national performance data, something we hear first-hand from frontline clinicians and something that is further evident in today’s survey findings.

“The results demonstrate how the stream of demand is continuing to drive lengthy waits, and cause difficultly for some patients in accessing information, emotional support and adequate pain relief.

“They also show the impact for staff when the number of people seeking urgent and emergency care is so high and resources are stretched.

“With pressures on services only likely to increase as we head into winter, ensuring the best possible experience throughout the entirety of the patient journey is a task that needs input from all parts of the health and care system.

“Over a third of people surveyed went to A&E before contacting another service and of those that did seek help elsewhere first, many said they were directed to A&E. We must support services in their efforts to collaborate locally, ensure a joined-up approach and help people to access the care they need, when they need it from the service that is best able to deliver.”

Dr Adrian Boyle, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, said the report shows that “patients are suffering the consequences of a system that is in crisis, while staff continue to shoulder the burden of delivering effective and safe care in these conditions”.

He added: “Issues within and outside the emergency department are negatively impacting patients’ experiences, as seen in this survey, with a high proportion enduring long wait times due to the lack of in-patient beds and inability to discharge people who are well enough to go home.

“No emergency department clinician wants to be treating a patient who is vulnerable and in need of care in a corridor and no patient wants to be put in this position. It’s degrading, demoralising and dangerous.

“The pressure in EDs will only continue to mount as we head into winter, when we know the inevitable spike in demand will hit.

“Those in power need to read the results of this survey, hear the voices of the patients who have expressed their experiences and concerns, and act on them now.”

Performance against key targets in England fell short in emergency departments and ambulance response times, according to figures published on Thursday.

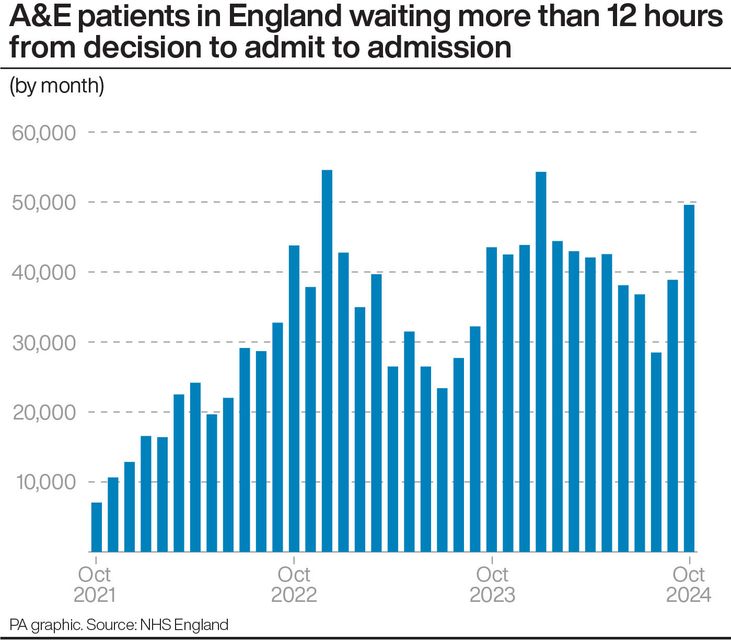

There were 49,592 people who had to wait more than 12 hours in A&E departments in October from a decision to admit to actually being admitted, up from 38,880 in September and the third highest monthly figure since comparable records began in 2010.

The number waiting at least four hours from the decision to admit to admission also rose, standing at 148,789 in October, up from 130,632 in September.

The average response time in October for ambulances dealing with the most urgent incidents, defined as calls from people with life-threatening illnesses or injuries, was eight minutes and 38 seconds.

This is up from eight minutes and 25 seconds in September and is above the target standard response time of seven minutes.

Ambulances took an average of 42 minutes and 15 seconds last month to respond to emergency calls such as heart attacks, strokes and sepsis – the target is 18 minutes.