Polls have closed in Algeria, where voters were deciding whether to grant army-backed President Abdelmadjid Tebboune another term – five years after pro-democracy protests prompted the military to oust the previous president after two decades in power.

Since Algeria announced the election date earlier this year, there has been little suspense about the result.

Though he is expected to be named the winner once the results are finalised, military-backed Mr Tebboune said after voting that he hoped “whoever wins will continue on the path towards a point of no return in the construction of democracy”.

With counting under way on Saturday evening, the question is less about who will win and more about how many voters stayed at home.

The results are expected late on Saturday or early on Sunday (AP)

Mr Tebboune’s backers and challengers all urged voters to come out to cast their ballots after boycotts and high abstention rates in previous elections marred the government’s ability to claim popular support.

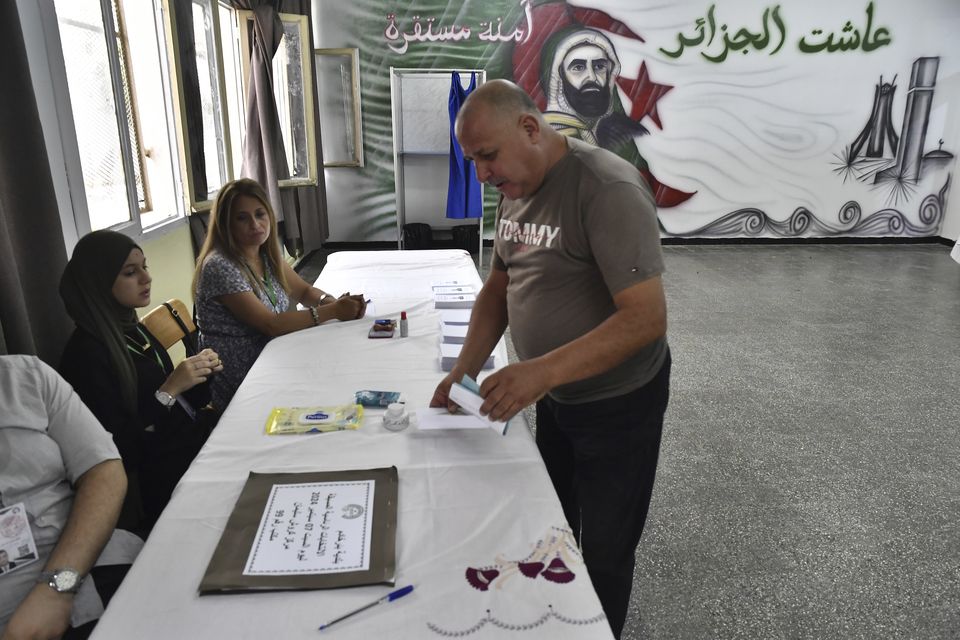

But throughout the day, many polling places in Algiers sat mostly empty, apart from scores of police officers manning their posts. Voters weren’t queuing outside in the summer heat waiting to cast their ballots.

However, polling places were kept open until 9pm local time on Saturday after officials extended the voting period to accommodate concerns that people may not have voted during the day in certain parts of the country due to the heat.

As of 5pm, voter turnout was 26.5% in Algeria and 18.3% for precincts abroad.

Preliminary results are expected later on Saturday night or early on Sunday morning.

Voter turnout is expected to be below 30% (AP)

Algeria is Africa’s largest country by area and, with almost 45 million people, it is the continent’s second most populous after South Africa to hold presidential elections in 2024 — a year in which more than 50 elections are being held worldwide, encompassing more than half the world’s population.

The campaign — rescheduled earlier this year to take place during North Africa’s hot summer – was characterised by apathy from much of the population, which continues to be plagued by high costs of living and drought that brought water shortages to some parts of the country.

“Uncle Tebboune,” as his campaign framed the 78-year-old, was elected in December 2019 after nearly a year of weekly “Hirak” demonstrations demanding the resignation of former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

Their demands were met when Mr Bouteflika resigned and was replaced by an interim government of his former allies, which called for elections later in the year.

Protesters opposed holding elections too soon, fearing candidates running that year each were close to the old regime and would derail dreams of a civilian-led, non-military state.

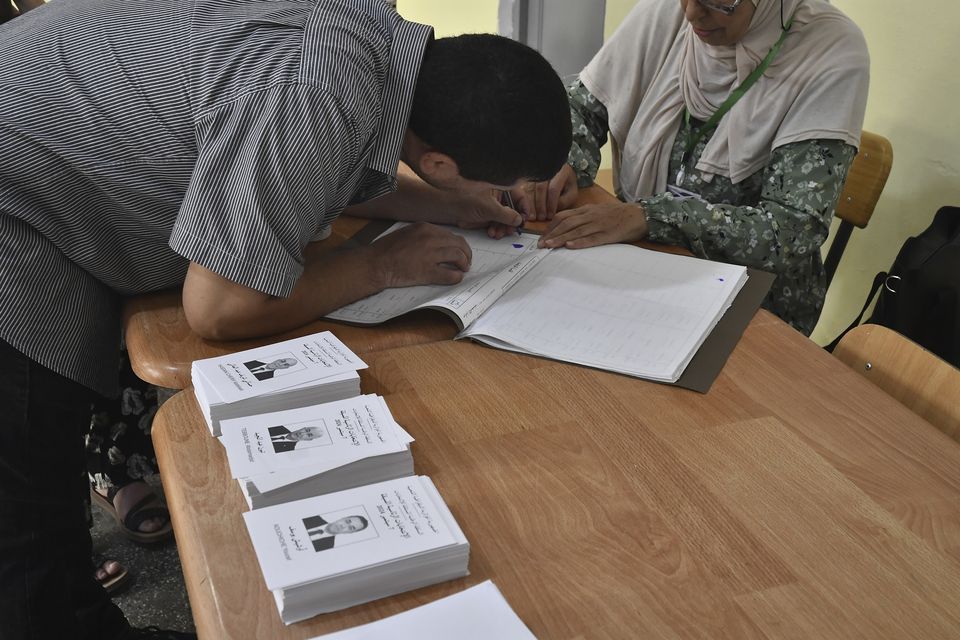

Counting is under way (AP)

Mr Tebboune, a former prime minister seen as close to the military, won the poll. But his victory was stained by boycotts and Election Day tumult, during which crowds sacked voting stations and police broke up demonstrations.

Throughout his tenure, Mr Tebboune has used oil and gas revenue to boost some social benefits – including unemployment insurance as well as public wages and pensions – to calm discontent. To cement his legitimacy, Mr Tebboune hopes more of the country’s 24 million eligible voters participate in Saturday’s election than in his first, when only 39.9% voted.

Twenty-six candidates submitted preliminary paperwork to run in the election, although only two were ultimately approved to challenge Mr Tebboune.

Neither political novices, they avoided directly criticising Mr Tebboune on the campaign trail and, like the incumbent, emphasized participation.

Abdelali Hassani Cherif, a 57-year-old head of the Islamist party Movement of Society for Peace (MSP) made populist appeals to Algerian youth, running on the slogan: “Opportunity!”

Youcef Aouchiche, a 41-year-old former journalist running with the Socialist Forces Front (FFS), campaigned on a “vision for tomorrow”.

Both challengers and their parties risked losing backing from would-be supporters who thought they were selling out by contributing to the idea that the election was democratic and contested.