When Alfred Hitchcock was a young boy, he claimed in a number of interviews that he was around five or six at the time when his father gave him a note to take to the local police station. An officer read the note and then locked him in a holding cell for a few minutes, telling him afterwards: “This is what we do to naughty boys.”

It was an experience that left him with a lifelong phobia of law enforcement. In an interview a few years before his death, he said he remained “scared stiff” of anything to do with the law and never even drove a car in case he got a parking ticket.

That experience in the cell also had another lifelong impact on Hitchcock: it steered him towards a genre of films in which characters found themselves in extremely uncomfortable, dangerous, unexpected and usually very confined or cramped situations.

In his first film as director, The Pleasure Garden (1925), the heroine is threatened by a man who has already murdered his mistress. In 1927, in his third film, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog, a Jack the Ripper-like hunt set mostly in fog, he set standards and styles for suspense that are still copied almost a century later. And that’s not bad for a man whose 125th anniversary will be celebrated on August 13.

He had originally wanted to be an engineer and in 1913 enrolled in night classes at the London County Council School of Marine Engineering and Navigation, where he studied mechanics, electricity, acoustics and navigation. His father died in December 1914 and Hitchcock, who never wanted to work in the family greengrocery business (which his older brother took over), went to work as a technical clerk at the Henley Telegraphand Cable Company until the First World War was over.

A still from the film ‘The Birds’ directed by Alfred Hitchcock (Photo by Universal Studios/Getty Images)

During his time at Henley, he took an interest in creative writing and in June 1919 was appointed founding editor of the in-house publication, The Henley Telegraph.

During this time, and to learn what worked in other publications, he began to read film trade papers and started going to the cinema on a regular basis, developing a particular fondness for directors such as Charlie Chaplin, DW Griffith, Buster Keaton and Fritz Lang.

It was the mechanics of filmmaking that interested him more than the cast. Indeed, he once said: “You must herd actors like cattle to get them in just the right placement in the frame, or with just the right expression for the reaction shot.”

He expected them to know their job on set and in the particular scene and rarely give them specific direction unless he thought something wasn’t working. He had a reputation for being difficult to work with, but some of the biggest names in the business — including Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman, Grace Kelly, James Stewart and Janet Leigh — would rearrange schedules just so they could be in his films.

Read more

He was still at Henley’s when he read that Famous Players-Lasky, a production arm of Paramount, was opening a studio in London. He applied for a job as a title-card designer (this was still the era of silent films, and he was good at drawing) and was hired to do the cards for The Sorrows of Satan. He was also encouraged to try his hand at art direction, co-writing and production management and worked on at least 18 films over the next six years before being handed the helm for The Pleasure Garden.

Even if Hitchcock hadn’t gone on to have such an extraordinary career, he would still be remembered as the director of Britain’s first film in sound — Blackmail. It had all the ingredients of what became the typical Hitchcock, including threat, murder and darkness and was also a commercial and critical hit in Britain, Europe and America.

As recently as 2017 it was listed in the top hundred greatest British films.

It had also another typically Hitchcockian ingredient: in a sequence set on the London Underground, he is seen being pestered by a young boy. That cameo is notable for being the first obvious appearance of the director in one of his films.

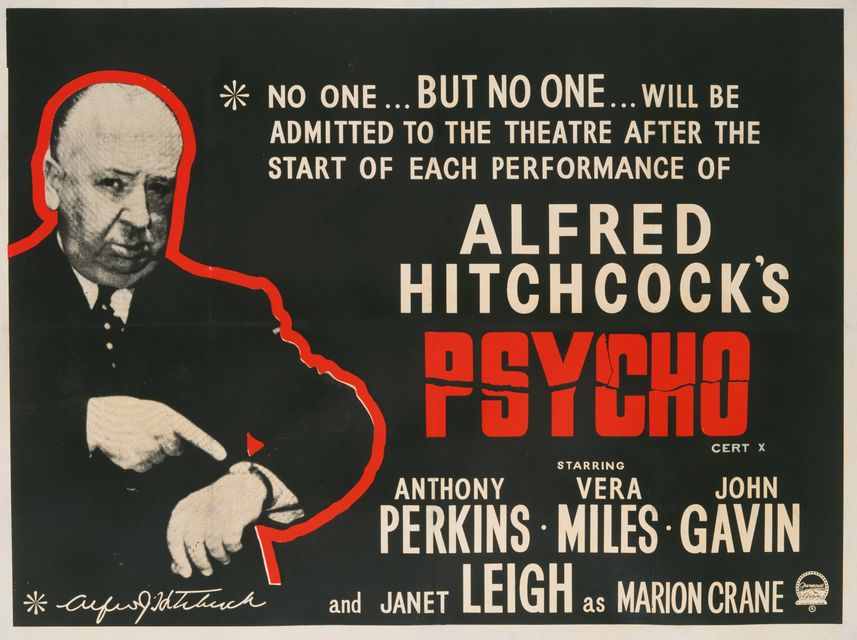

A poster for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 horror film ‘Psycho’ (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

None of his next few films were particularly remarkable, apart perhaps from the first ‘talkie’ version of Sean O’Casey’s Juno and thePaycock in 1930, which featured the yet-to-become-legendary Barry Fitzgerald as The Orator. Hitchcock was, as he described it, “dabbling” at this point of his career, as was most of the film industry (including cinemas themselves) while it adjusted to the still stumbling era of sound.

The big breakthrough came in 1934 with The Man Who Knew Too Much (about spies and criminal conspiracies), starring Nova Pilbeam, Peter Lorre and Leslie Banks. He made a second version in 1956, with James Stewart and Doris Day, but it is this one which deserves to be remembered as the first truly, quintessentially Hitchcockian film.

He would, of course, make better ones, but all of the pieces he had been dabbling with since 1919 came together for the first time. And that includes what became known as the McGuffin: “…an object, device or event that is necessary to the plot and motivation of the characters, but insignificant, unimportant or irrelevant in itself”. There are almost as many McGuffins as cameos in his films.

A year later came his version of John Buchan’s The 39 Steps. I have lost count of the number of versions I have seen since I first started watching when I was around 12, in 1967, but I still regard this as an almost perfect film. Buchan himself described it as “better than the book”, Orson Welles proclaimed, “Oh, my God, what a masterpiece,” and Robert Towne (who wrote the Oscar-winning screenplay for Chinatown) remarked: “It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that all contemporary escapist entertainment begins with The 39 Steps.”

Jimmy Stewart, Grace Kelly and Alfred Hitchcock

The film was a huge commercial success and was followed by a slew of successes from then until 1959, including The Lady Vanishes, Jamacia Inn, Foreign Correspondent, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Lifeboat, Strangers on a Train, Dial M for Murder, Rear Window, Vertigo and North by Northwest. Each new Hitchcock film was an event in its own right, not least because he, too, had become an event in his own right — fawned over by filmmakers worldwide, hugely influential on the work of others, and his Alfred Hitchcock Presents/The Alfred Hitchcock Hour television series an enormous success.

I’m not a great fan of Psycho (1960) — even though it became his best-known and most financially successful film — or The Birds (1963), where the effects looked naff even then. But both remain watchable because each contains some classic Hitchcockian moments, as did his final five, Marnie, Torn Curtain, Topaz, Frenzy (his worst film) and Family Plot (mostly unjustly overlooked or completely forgotten today).

His was a long and extraordinarily successful career (1919-1976), even though he never won an Academy Award for direction. At the 1968 Academy Awards he was presented the Irving G Thalberg Memorial Award by the Academy’s Board of Governors. His acceptance speech was short: “Thank you very much indeed.” As in so many of his best films, he delivered his blow brutally and quickly.